By: Marilyn J. Wooley, Ph.D.

Providing CISM services in rural areas presents challenges and means not only braving treacherous travel conditions but appreciating rural values and perspectives.

Providing CISM services in rural areas presents challenges and means not only braving treacherous travel conditions but appreciating rural values and perspectives.

1. GETTING THERE: Rural CISM can be a long, strange trip

Rural roads, unlike freeways, don’t provide rest stops or regular services. Maintenance is erratic. Pavement regularly narrows into one-lane or melts away entirely. Driving involves negotiating serpentine roadways with unstable shoulders and truckers who propel fully loaded logging rigs around sharp curves at breakneck speeds. Deer and tumbling boulders materialize directly in your path forcing your vehicle toward precipitous cliffs that plunge into raging rivers. Occasionally, landslides large enough to swallow a school bus wipe out a section of highway. During fire season, wind-driven wildfires blow suffocating smoke and live cinders across roads. In winter, snowfall can completely cut off towns and strand motorists. A 4-wheel drive vehicle is de rigueur for country driving, but even they get stuck.

Air transportation is also a challenge. Redding, California in 1979, the year I moved to Shasta County, was considered rural. The airport was little more than a Quonset hut with a hot dog stand. A 9-passenger turboprop arrived at the sole gate twice per day from San Francisco. If the plane broke, as it did my first trip, the hapless passenger would be stranded for as long as it took to fix it. Upon departure, passengers were introduced to the uniformed pilots on the tarmac as they personally loaded any item bigger than a briefcase into the cargo hold.

Air transportation is also a challenge. Redding, California in 1979, the year I moved to Shasta County, was considered rural. The airport was little more than a Quonset hut with a hot dog stand. A 9-passenger turboprop arrived at the sole gate twice per day from San Francisco. If the plane broke, as it did my first trip, the hapless passenger would be stranded for as long as it took to fix it. Upon departure, passengers were introduced to the uniformed pilots on the tarmac as they personally loaded any item bigger than a briefcase into the cargo hold.

Redding Municipal Airport has grown and is now served by 3 airliners with jet engines, that offer 8 destinations, two of which have daily connections. The remainder depart weekly, approximately as often as a yester-year stagecoach. The airport still has only one gate, but there is a good Chinese restaurant. The best part of flying from Redding, aside from landing safely at the destination, occurs during lift-off as mind-blowing vistas of snow-capped Mt. Shasta to the north and Mt. Lassen to the east emerge against a cerulean sky. The view more than compensates for other challenges.

Still, airports in most rural towns are not served by airlines or even traffic control towers. As a result, State agencies have flown me to remote towns in a 4-seat Cessna. The pilot is good natured and lets me sit up front and watch him switch radio frequencies and look for other aircraft, such as wildland fire spotter planes and air tankers.

Flying above wildland fires offers an eerie view. Opaque smoke blankets the ground. In the distance, massive white clouds billow more than 10,000 feet above the dreary horizon—the sign that major wildfire is active below. On one recent trip the pilot ascended to more than 13,500 feet to avoid the smoke. The cabin is unpressurized, so we deployed oxygen masks.

Flying above wildland fires offers an eerie view. Opaque smoke blankets the ground. In the distance, massive white clouds billow more than 10,000 feet above the dreary horizon—the sign that major wildfire is active below. On one recent trip the pilot ascended to more than 13,500 feet to avoid the smoke. The cabin is unpressurized, so we deployed oxygen masks.

Flying over mountains on clear days offers views of lush green foliage surrounded by hundreds of acres of blackened, claw-like tree skeletons, the aftermath of recent fires. Older burn scars reveal bright-green brush bursting through decaying trees following the natural succession of the post-fire landscape. Snaking through it all are old logging roads and rivers.

2. BEING THERE: Once you arrive at the CISM site, the challenges are not over. Be prepared for issues not experienced in the big city.

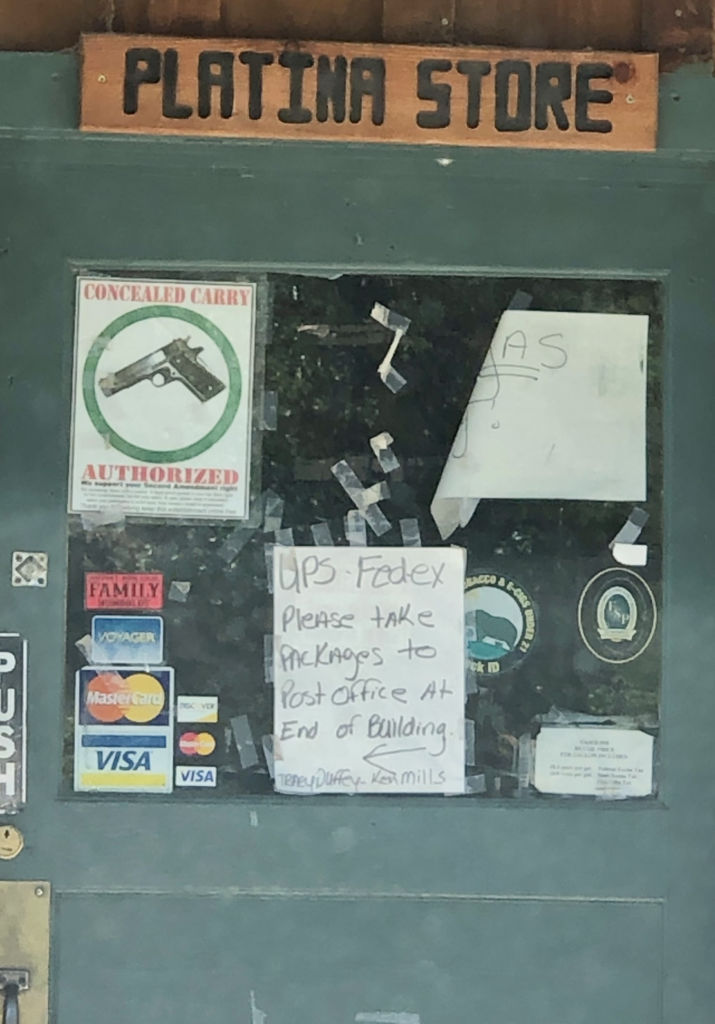

POLITICAL ATTITUDES: Leave them at the door

COVID vaccinations? Not in the conservative, fiercely independent “State of Jefferson” where “Don’t tread on me” is proudly displayed on T-shirts, bumper stickers, and front porches. What is the protocol when entering a department where few are vaccinated and all refuse masks? I once suggested to a commander that the CISM participants wear masks and was sternly advised, “We’re all adults here. We make up our own minds.” Despite State regulations, they remained unmasked. The bottom line: If I choose to serve first responders in many rural areas, the best I can do is protect myself. That said, when I ‘ve asked them to mask up in my office for a 1:1, everyone has graciously complied.

TEAM CONFIDENTIALITY: Where everyone knows your name

In small communities everyone in every agency knows everyone else in every other agency. Furthermore, as a clinician with a practice specializing in evaluating and treating first responders, running into individuals I know is common during CISM.

One hot summer day, I arrived to a CISM in a remote area for an OIS that occurred during an active wildland fire. Hundreds of marijuana farmers, who vehemently didn’t want to abandon their soon-to-be incinerated grows, were being evacuated. As LEOs fought chaos to direct traffic and firefighters staged to fight the conflagration, one of the heavily armed evacuees decided to open fire on the responders. It was not a good idea.

One hot summer day, I arrived to a CISM in a remote area for an OIS that occurred during an active wildland fire. Hundreds of marijuana farmers, who vehemently didn’t want to abandon their soon-to-be incinerated grows, were being evacuated. As LEOs fought chaos to direct traffic and firefighters staged to fight the conflagration, one of the heavily armed evacuees decided to open fire on the responders. It was not a good idea.

The agencies involved in the resultant CISM included Fish and Wildlife, CalFire, and the local Sheriff’s Office. As I entered the room, I realized the responders to be debriefed included a LEO I had performed a pre-employment psychological evaluation on, a long-term client I was treating for PTSD, and a client I had recently accepted into my practice. Furthermore, a new peer support team member was a former client. I couldn’t have predicted all these complications. The thought flashed through my mind: “Should I have gotten a list of participants beforehand to screen out the individuals I’d had previous contact with?” Of course not. I decided to greet them as I usually do and proceed with the CISM protocol. Everyone shared and behaved professionally. It worked out just fine.

BUILDING RAPPORT: Watch your mindset

Rural individuals tend to be down-to-earth. An impersonal presentation by a CISM team will be interpreted as demeaning. Warmth and concern increase cooperation and trust. I once observed a colleague approach a group of wary, rural individuals. Suddenly, he morphed from a straight-backed, direct-gazed, city professional into a boot-shuffling, slow-talking, awe-shucks type with his thumbs hooked in his belt. As my jaw dropped, he established instant rapport with the crowd. Reading the room is essential before doing CISM in rural areas. Folks may seem “one-down,” but they aren’t uneducated or simple. They’ve developed vast knowledge and rural “street sense” having to make do with far fewer resources and essentially no outside help. Rural first responders are generalists by necessity and good at their complicated jobs. They must be, or they don’t last long.

FLEXIBILITY DURING THE CISM: Be prepared for anything.

CISM rules may have to be modified in small departments. For example, resources may not be available to cover duties during CISM. Tones may go off and occasionally participants may be called out. Depending on the circumstances, the department may want to reschedule the team could offer follow up.

The likelihood of rural first responders knowing victims, be they friends, coworkers, or even family members, is highly likely. Rolling up to a call and recognizing a vehicle involved in a crash or knowing the family who lived in a house fully involved in flames, or a responding to a suicide of a friend’s child is devastating and among the most stressful events experienced by first responders. The entire department may be affected because of close attachments. In such a CISM, the team should expect, and normalize, emotionality long before the Reaction Phase of the Debriefing.

At the same time, expressing thoughts and reactions in a close-knit group can be tricky. In a small town or organization everyone knows your business. Participants may resist sharing their concerns or doubts for fear of censure or judgement. There is a need to fit in coupled with strong peer pressure to conform and little room to speak out. In addition, underlying organizational issues/departmental politics may arise and must be handled with finesse. In both these cases, offering responders time for one-on-one discussions with team members or MPH may be helpful. Checking in with the Chief before and after the CISM to assess the status quo is crucial. They are affected, too, and need support to help their people.

In the Symptom Phase, attending to participants personally rather than reciting a list of symptoms makes a powerful connection. Similarly, introducing information regarding interpersonal relationships in the Teaching phase, such as normalizing differences in individual reactions and offering suggestions on coping with the emotional reactions of responders’ family members fosters bonding and may help alleviate potential tensions.

Finally, encourage group cohesiveness. Even when a call has a poor outcome, emphasize that the response team worked together and supported each other. To end Debriefings on an upbeat note, I ask, “Was there anything about the way this incident was handled that made it better (or in the case of a bad outcome, not as bad as it could have been?)

CISM in rural areas is challenging, but also offers adventure, awe-inspiring scenery, interesting people, and gratification at serving the underserved. It’s been my honor to provide it.

Further Reading:

D’Andrea, L. M., Abney, P. C., Swinney, R., & Ganyon, J. R. (2004). Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD) in rural communities. Traumatology: An International Journal, 10(3), 179-187.